After Japan, everything changed.

(See On Air: My First Trip to Japan (and the First Giant Balloon Sculpture I Ever Built) for more on that.)

The Nebuta sculpture in December of 1998 had pushed balloon art into new territory—and people noticed. Not just friends, fellow balloon twisters, and balloon distributors. I already had their attention through BalloonHQ.com, the online community I was running. (Don’t bother looking for it now. Facebook and the introduction of social media eventually changed how our tribe communicated. That’s a story for a future post.) But now event organizers and artists from around the world were noticing art with balloons—and me. I wasn’t just a guy making latex sculptures anymore. I was becoming the person others would rally around when it was time to dream bigger. When it was time to build community sculptures. When it was time to do community art projects.

A Record-Setting Idea Takes Shape

Leo, a balloon distributor from Belgium, approached me during TJam, the first balloon twisting convention. He wanted to launch a European version of the convention that would attract artists from across Europe and beyond. But he knew that to pull in international attention, he needed more than workshops and lectures. He needed a spectacle. He wanted to host the largest balloon sculpture the world had ever seen, timed to coincide with the Euro 2000 soccer tournament. The goal: a giant balloon soccer player, big enough to get noticed, and bold enough to land in the Guinness Book of World Records.

At the time, I was the only person who had attempted anything close to the scale that Leo envisioned. Knowing this project would be larger than what I had done so far, I knew I needed to recruit help. I turned to someone I trusted: Royal Sorell. Royal was a wildly creative and technically brilliant balloon artist. We had been experimenting with new large-scale construction techniques together. I could lead the project and crew. Royal could design and build in ways that made jaws drop. And when I asked him to partner on this, he didn’t hesitate for a second. He was in.

Of course, there were others that were needed as well. Royal’s role was clearly defined. He was going to work with me on technique, design, and helping to build a visual language of balloon art we could use to share plans with the non-English-speaking team members. Enter Todd Neufeld, a recurring character throughout my project stories. Todd is the guy I always needed when I didn’t know what I needed. He’s a great idea guy that to this day helps me work through random planning, leading teams of artists or community members, catching juggling clubs I throw at him while crossing streets in Pittsburgh, and just offering general support. He also had the really unique but highly critical job of helping to manage Royal. I loved Royal, but he was always a handful. Todd had a rare talent for creative triage, whether it was wrangling logistics or, in this case, gently steering Royal back on task when his creative energy went sideways. So I called Todd to help, knowing that he’d jump at the opportunity to fly to Belgium. To my surprise and disappointment, Todd informed me that he needed to remain a phone call away on this one. He had just completed his law degree and had to study for the bar exam at that time. But he did help plan. The project was still going to go on.

Dress Rehearsals: Twist & Shout and IBAC

Tom, who ran the first TJam, announced he wouldn’t repeat the convention in 2000—he didn’t want to tempt fate with possible Y2K chaos. But where one door closed, another swung open: Royal and his wife, Patty, jumped up to save the newly established precedent of a balloon convention in February. They launched their a brand-new convention called Twist & Shout that would take place in February 2000. That turned out to be the perfect chance for us to test our ideas in public. We built a large sculpture in the lobby of the convention hotel. Not nearly as large as the world record one to come, but it was a critical step. It was training, research, and proof that we could scale these ideas even further.

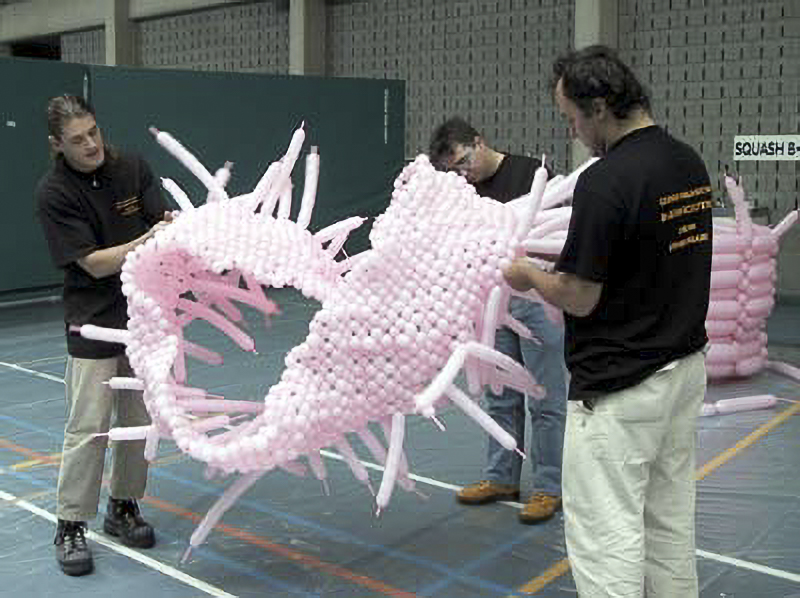

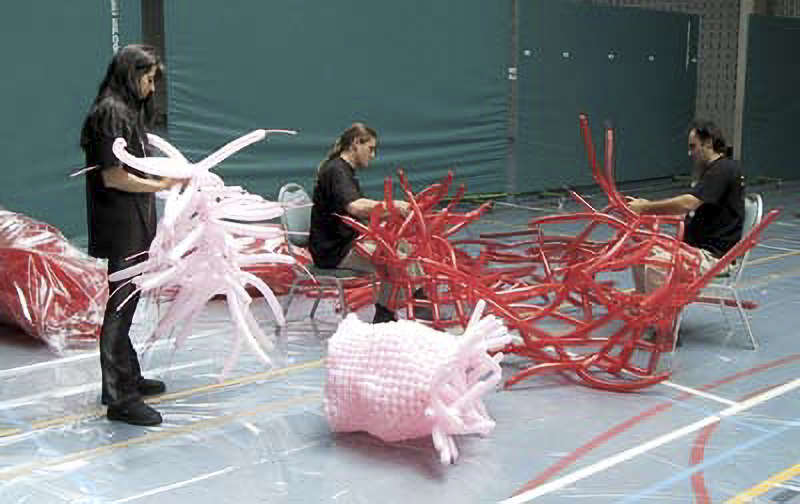

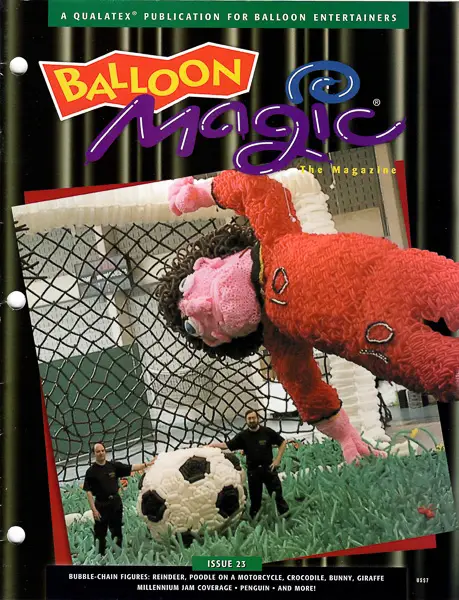

In March 2000 we had our second practice round when the International Balloon Arts Convention took place. That was an annual convention for balloon decorators. Royal and I, along with other balloon twisters, made a great showing in the IBAC competition with a large twisted sculpture unlike anything that had been seen before. That allowed us to refine what we had just tried at Twist & Shout. While the February convention allowed us to test the new techniques, the March build let us focus more on managing the jobs of crew members. We learned things like how fast we could expect crew members to work, how to keep them focused on tasks, and what our stamina would be when working on something for multiple long days. We didn’t win the competition. We were told that it really wasn’t judgeable by the standards they used for years in that contest. It was just too different. But we didn’t care. It turned heads, and we got the cover of the next issue of Balloon Images Magazine.

Welcome to Mol

Before we knew it, June arrived. We gathered at a resort in Mol, Belgium, where the sculpture would be built. As mentioned earlier, it would be the centerpiece for the convention, Millennium Jam. Our gargantuan soccer players were a tribute to the Euro 2000 soccer energy found all over Europe, even though we weren’t officially connected to the tournament. The timing was perfect.

My build team consisted of 45 artists from 10 different countries that came at their own expense to be part of this world record sculpture. As I walked into the hotel, I saw a few people I knew, but many more that I didn’t. And one person that I knew very well but never expected to be there: Todd. He decided he couldn’t miss this one-of-a-kind event for something as insignificant as the bar exam. When I approached him he said, “I can take the bar exam any time. I’ll never get a chance to be part of something like this again.”

Spoiler: while Todd was right about being able to pass the bar later (which he did), he was wrong about never being part of massive sculptures again.

Most of the people who joined the volunteer crew had seen the Nebuta project and were eager to be part of something just as ambitious. It was a wildly mixed group. Their experience with balloons ranged from seasoned pros to enthusiastic newcomers. Few of them knew each other. They came from ten different countries, many traveling alone, with no clearer idea of what to expect than I had. Royal and I were going to have to be clear, focused, and fast on our feet to shape this ragtag team into a cohesive build crew.

The linguistic landscape consisted of at least 7 different languages spoken on site. Giving instructions was like a high-stakes game of telephone. I’d explain a process in English. It would pass through, perhaps, a German speaker, then a Dutch speaker, then someone who understood a mix of French and Spanish—and by the time it reached the person that needed the instruction, I could only hope the result resembled the initial directions. Somehow, it worked.

Game day

We were aiming for the record of “Largest non-round balloon sculpture.” That meant everything had to be constructed using twisting balloons—no large inflatables, and no framing allowed.

To meet the requirements for a Guinness record, we needed evidence of our accomplishment. And that’s where Patty came in. She managed our balloon inventory. Even though we knew exactly how many balloons we had going in, Patty clicked a handheld counter every time someone took a new bag. She kept paper records too. Guinness required precise inventory documentation, and Patty’s meticulous tracking ensured we had it.

The whole project took a year to plan, but only 5 days to build. That’s how balloon art works—the medium is short-lived, so you plan ahead and build fast. Starting on day four, we worked around the clock. No more sleeping, no more play. By day five, tension was high and nerves were fraying. But we were going to finish on time– almost.

Unexpected hurdle

Leo rented a scissor lift and had it on site before we began construction. He didn’t know when we’d need it, but we knew that eventually we’d be working on a sculpture taller than five crew members standing on each other’s shoulders, and those particular acrobatics weren’t going to be possible to complete it. Since we didn’t need the lift until we reached the point of final assembly, no one bothered to test it when it arrived. You can guess where this is going. It was the Sunday. The rental company was unreachable. We were stranded, with soccer player body parts all over the floor instead of forming complete human bodies. It resembled a horror movie more than a piece of art with arms, legs, heads, torsos, and everything else scattered across the floor.

I had wanted this to be a community build because I knew we’d have fun working together. The diverse crew came with a bonus. Everyone has different skills. Patrick Brown, one of the artists on the team, pulled out his multitool and uttered what might be the most heroic sentence ever spoken at a balloon build: “I’ve got this!”

No one else had a clue what to do. Patrick did. It turned out that fixing hydraulic lifts was something Patrick did at his day job. He fiddled, poked, and somehow, miraculously, got the lift running again. Crisis averted. Lesson learned: Every crew for future big builds must have someone capable of repairing equipment.

A Gargantuan Effort

We constructed two soccer players, each about 40 feet tall, in an active pose. Because of the angle of the figures, the sculpture stood around 25 feet high overall, and stretched roughly 80 feet wide and 40 feet deep. Even the grass was balloons. Not a single bit of framing was used to hold its shape. We just had a few internal pipes to help suspend the sculpture in the air. (Imagine straight pipes running through bodies so we could tie suspension lines to something other than easily breakable latex balloons.) Everything was twisted together as one continuous structure. Over 40,000 twisting balloons were used.

When the sculpture was complete, the convention began. Artists from around the world walked in and saw the massive centerpiece we’d created. It was everything we’d hoped for. It even looked remarkably like our drawings. Photos, articles, and interviews went everywhere.

When Guinness Blinks, Ripley’s Believes

After most of us returned home from the convention, Leo submitted all of the video tape records, the written documentation, photos, and everything else we had, to prove a record had been set. Time passed. We received a letter from the Dutch Guinness office (the office most local to where we were in Belgium) saying we had accomplished our goal, and we’d hear from London soon. But the letter and certificate from London never came. When we followed up, the main office said they knew nothing about any record we claimed to have set. And with no official record, there was no certificate. Just a shrug from across the Channel.

A few months later, despite a lack of interest from Guinness, Ripley’s Believe it or Not! reached out to us to do a segment on their show. Only after the success of the Ripley’s appearance did the producers of the Guinness TV show call. Now they wanted to feature the project.

“But we were never granted the record,” I told them. “I tried. I have the letter, the documentation. I followed every rule.”

The producer replied, “I have a show to make. I need stories people want to watch. If I say it’s a record, it’s a record. We’ll sort it out.”

We never got the chance. The Guinness TV show was canceled before anything about us aired.

But that line, “If I say it’s a record, it’s a record,” came back to me later.

Years after Belgium, a small Airigami team built a 6-meter-tall LEGO minifigure out of balloons in London during a LEGO show. Some of the most intricate and creative sculptures built with plastic snap-together bricks filled a giant convention hall. “People are coming to see LEGO sculptures, but LEGO bricks are small. The hall is big. We need something that fills the space and lets people know what this show is about,” we were told by the show’s organizer.

The editor of the Guinness Book of World Records was in attendance. He approached me. This was my chance to ask, in person, how to get recognition for the soccer sculpture. He brush off the question, but followed with, “I need to include this in the book,” as he pointed at the LEGO guy. “This has to be a record, right?”

“No, it’s not,” I told him. “It’s not the biggest, or the tallest, or the most anything. It’s just a fun sculpture to fit the theme of a LEGO show.”

He smiled. “I need to sell books. If I say it’s a record, it’s a record. We’ll sort it out.”

And sure enough, the LEGO figure was later listed in the Guinness Book as the Largest LEGO Minifigure Made Out of Balloons. Which, let’s be honest, is a weirdly specific but very real category. It was also credited to only me. No mention of the crew. No mention of my wife, Kelly, who actually did all of the design work on this. But at least Airigami finally had a record.

The soccer player sculpture never got its certificate. But it did get built. It did bring people together from all over the world. And it did prove something important: If you twist enough balloons, if you rally enough artists, and if you keep going even when the equipment fails, you can set a record, whether Guinness acknowledges it or not. But we didn’t need a certificate to know what we’d done. Believe it or not, we just needed balloons, community, and a little bit of collective joy.

2 thoughts on “How Big is Big?”